“My life, like my artwork, is untamed, like a wild horse running free”

Zhou Yunxia (周云侠) was born in 1958 in Shanghai, with his ancestral home in Ningbo. He did not enjoy city life as a child, and when his family moved to Nanjing to support the development of inland areas, he had the opportunity to get closer to nature and the countryside. Influenced by his older brother, he developed a love for painting and began his artistic growth as an amateur in a youth art class.

In 1975, when he graduated from middle school, the "Educated Youth Movement" had already been going on for seven years, and he was inevitably sent to the countryside near Nanjing as part of this era's massive social campaign. In the rural areas, his artistic talents became apparent, and he was often involved in political propaganda work such as creating artistic lettering, blackboard reports, cartoons, and themed artwork. His skills led to his transfer back to Nanjing in 1979.

The resumption of the college entrance examination in 1977 marked a significant transformation for China. For many "educated youth" who had spent valuable years in the countryside, going to university was an opportunity to change their fate. Zhou Yunxia attempted the exam twice. Despite excelling in his major subjects, he was unable to gain admission due to his poor scores in Chinese and politics, which was a common fate for many artists of his generation.

At that time, Zhou Yunxia had a stable job, but he believed that one could still become an artist without entering an academic institution. In order to have more time for painting, he resigned from a relatively well-paid position at a propaganda organization, where he was required to work in an office. Instead, he trained to become a chef so that he could have more free time after completing his designated tasks. This way, he could devote his spare time to his creative work without constraints.

Because he was employed by a "unit," Zhou Yunxia had his own living space and a dedicated area to paint, which was highly enviable during that era. As a result, many like-minded peers often gathered at his place, finding warmth in each other’s company while experiencing an idealized sense of independence and freedom. The young people were eager to share or show off new ideas in literature, painting, poetry, and music, and their passion, which had been suppressed for so long, made them feel they had transcended the backward reality and mundane society, which they took pride in.

With the gradual opening of China’s doors to the outside world, these young intellectuals were introduced to fresh and stimulating Western art through printed materials and major exhibitions from Europe and the United States. This group of young people immediately began to reflect on and practice the transformation and reform of art and culture. Innovation and originality became their natural mission. However, this process was not a consensus within society at the time. Compared to the loosening and opening of the political and economic fields, the cultural and artistic spheres were objectively in the process of recovering from the Cultural Revolution’s devastation. In terms of both system and ideology, the official call for literature and art to serve the workers, peasants, and soldiers, as well as political movements, continued for a long time. The Soviet-style artistic framework still dominated due to its inertia.

In the 1980s, China's market economy was just beginning to take root, and few people could find a way to survive outside the system in the field of culture and art. Leaving a "unit" and living independently would face enormous difficulties.

It was in the contradiction and conflict between ideals and reality that artists, both middle-aged and young, living in different cities, embraced the impact and baptism of new artistic concepts. From Millet and Courbet to Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, from Cubism, Expressionism, and Abstract Painting to Dadaism, Futurism, and Surrealism, from post-World War II Abstract Expressionism to Minimalism and Pop Art, and finally to the diverse postmodern thoughts and creative practices of the 1980s, these ideas were introduced and introduced to China as society opened up and the economy developed. This process began in the late 1970s and continued until the early 1990s.

Against this cultural backdrop, Zhou Yunxia discovered Belgian painter James Sydney Ensor (1860-1949) and American artist Thomas Hart Benton (1889-1975). These two artists were vastly different, but both focused on social groups, with works that strongly referenced reality, characterized by intense and noisy shapes and colors. Ensor was a precursor to European Symbolism and Expressionism, while Benton was a representative of American regionalism and the mural movement. Their inquiries into society and reality were completely different from the Chinese traditional notions of "literature carrying the way" and "gentle and kind-hearted."

Zhou Yunxia’s works in the 1980s were deeply infused with a sense of crisis and humanistic concern. His painting language was unconstrained, intense, and extreme. In general, these characteristics can be seen as his response to Western art represented by these two artists.

This distinct stance and resolute attitude was not only a rebellion against the official system and Soviet-style art, but also a response to the stagnation and decline of traditional Chinese art forms at the time. In fact, when Zhou Yunxia first became interested in art during his youth, influenced by his older brother, what he encountered and began to practice were precisely the traditional forms of Chinese art. He often recalled how he would habitually lean against the window of a famous mounting shop in Nanjing, watching the mounting master handle the artwork, mesmerized to the point of losing track of time. He spent all of the three yuan in pocket money his mother gave him each month on Xuan paper and brushes. Without a writing desk at home, he would mount the Xuan paper on the mud wall and paint on it.

However, after returning to the city from the countryside and being exposed to new artistic concepts, the young Zhou Yunxia felt that those "peonies and lotuses" were completely out of place with his own sensibilities. In his understanding, "beauty" could not be anything other than the transformation of the soul through painful struggle. Yet, the influence and training he received from his early years enabled him to master traditional materials such as Xuan paper and brushes, which he would continue to incorporate into his creative work at various stages in his later career.

Zhou Yunxia participated in the 1985 "Large-Scale Modern Art Exhibition," the 1986 "Sunbathing" exhibition, and the 1989 "Nanjing Free Artists' Five-Person Exhibition." During this time, he also met Mr. Hans van Dijk (1946–2002), a Dutch scholar and curator living in Nanjing, with whom he maintained long-term contact. Another significant activity during this period was his exploration of the human geography and historical culture of mainland China. Zhou Yunxia, along with several other painters, traveled to regions such as the Tanggula Mountains and the Tuotuo River in Qinghai, Dunhuang, northern Shaanxi, and Xi'an.

Unlike his fellow artist Ding Fang, who immersed himself in the "cultural fever" of the time, Zhou Yunxia did not fully devote himself to the passion for exploring the nation's cultural history. Instead, he continued to focus on the modernity of painting language and how to portray the living conditions of people in an urban context.

Entering the 1990s, many art collectives across the country began to disband, and social life was confronted with different themes. Some artists started focusing on everyday experiences, expressing their personal interpretations of reality through individual approaches derived from their painting language. Zhou Yunxia, however, was somewhat lagging behind in this context. For him, the tragic hero era had not yet ended, and humanity's collective fate still hung like a sword over their heads.

In 1991, he held a solo exhibition at the Beijing Concert Hall Gallery. In the preface, critic Li Xianting remarked that Zhou Yunxia "places his personal life experience within the larger context of society and even culture, giving his emotional outbursts a certain cultural significance." In that same year, Zhou Yunxia resigned from his job as a chef to become an independent artist. He continued with the style of his previous works, occasionally introducing elements of abstraction and composition into his paintings. It wasn't until 1994, when he moved to the Beijing Yuanmingyuan Artist Village, that he began to undergo a transformation.

The Yuanmingyuan Artist Village was, for many young artists, like a "revolutionary sacred place" akin to Yan'an, a symbol of the ideal state of independent existence outside the system. The village became a space where artists could interact with one another and exchange ideas, providing a platform for refreshing their concepts. In these discussions and exchanges with his peers, Zhou Yunxia began exploring expressions of the everyday. Along with other artists, he referred to their approach as "Chinese Comedy Style," which was later dubbed "vulgar art" by theorists.

Their works depicted the mundane aspects of daily life—meals, clothing, shelter, and the trivialities of daily routines—conveying a sense of boredom and absurdity. The images appeared flashy and tacky, and the rhetoric was marked by imitation, satire, and parody. These works were, in fact, a branch and evolution of Pop Art, which later became commonly labeled as "kitschy art."

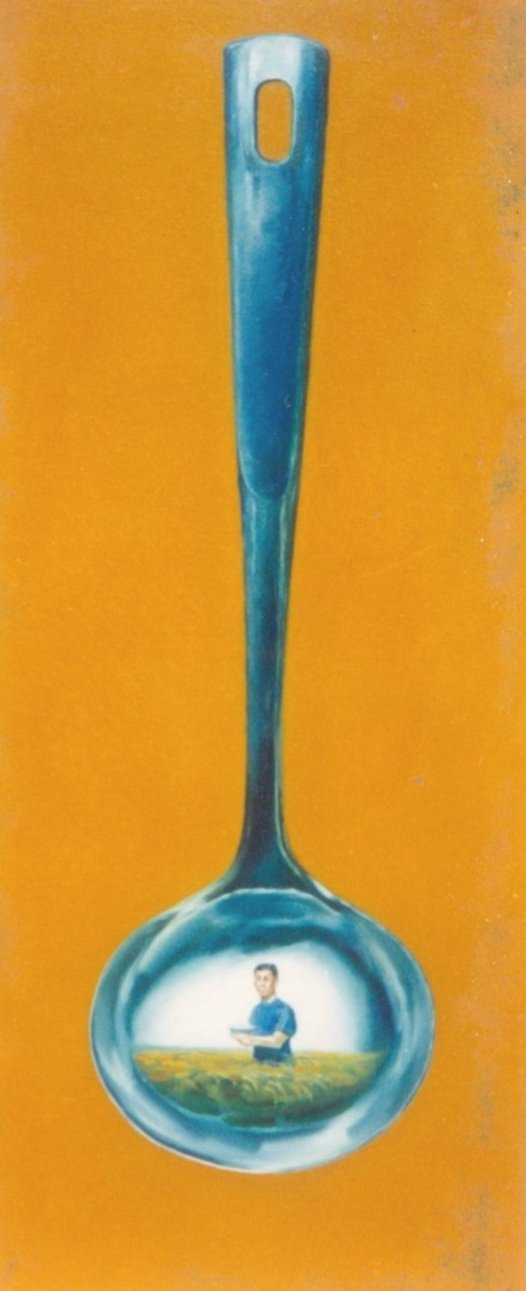

Zhou Yunxia transitioned from the tragic themes of "spirit and flesh" to the satire of secularism, with the spirit of Surrealism playing an internal role in his work. Corresponding to this shift was a renewal and transformation of his painting language. As "kitschy art" became increasingly popular and deliberate in the art scene, Zhou Yunxia decisively stopped creating in this phase and returned to addressing the fundamental issues of painting language and art itself.

Having passed the age of forty, he was more inclined to confront his true self in solitude. In 2002, Zhou Yunxia moved his studio to Shanghai, marking the beginning of a new phase in his artistic career, one focused on maturity and growth.

From 1999 to the early years of the new century, Zhou Yunxia began to reconsider the issue of ethnic identity within cultural context. Through various forms of artistic practice, including the transformation of ready-mades, site-specific installations, performance art, and the use and transformation of special materials, he significantly expanded the creative space. Stimulated and influenced by postmodernist ideas and reflections, Zhou sought to find his starting point and attitude as an independent contemporary artist. He also began incorporating accessible resources from his surroundings to engage in deeper and more intrinsic artistic expression.

In this process, reflection on and re-examination of traditional Chinese art forms played a significant role. Zhou Yunxia scanned the inner meaning and language of ancient art through a contemporary lens, drawing from the classical examples within traditional culture that he was drawn to, and then transformed them into his unique artistic language. For example, in his focus on the Han Dynasty’s "golden-threaded jade burial suit," Zhou Yunxia developed works that featured costumes constructed from Mahjong tiles, a juxtaposition of structure and form, while also translating this concept into a visual language of points and lines, which interacted and expanded across the canvas.

Similarly, in his exploration of traditional Chinese ink painting, particularly the most culturally and aesthetically profound forms of traditional ink, he employed surreal freedom in composition and abstract tension in his brushwork, creating a contemporary vibrancy.

This return to the essence of artistic language was deeply rooted in Zhou Yunxia’s unwavering dedication to modernism, allowing the core and concepts of his works to continue the experimental and avant-garde spirit that he had begun in the 1980s.

After moving his studio to Shanghai, Zhou Yunxia discovered the nearby town of Zhujiajiao during an incidental trip. He quickly relocated his studio from the factory district in Pudong to this picturesque water town in Jiangnan, which had not yet been developed for large-scale tourism at the time. This move attracted many other artists to settle in the area as well. Zhou Yunxia reconnected with the closeness to nature he had experienced in his childhood, harmonizing his life and work with the local customs and environment.

Although the material conditions were still modest and challenging, with little difference from his time in the Yuanmingyuan Artist Village, Zhou Yunxia, having weathered many storms in life, was able to find contentment in simplicity. He lived there for over a decade, embracing the hardships and deriving joy from them. In particular, he discovered and began using discarded frog skin, a food waste material, to create his artworks. Moving from flat to three-dimensional forms, he viewed these works as a denunciation of humanity's destruction of nature's harmony due to unchecked desires. On an artistic level, these pieces also reflected his critique of the narrow and limited mechanisms of aesthetics and visual culture.

Since the 1980s, there has been an implicit thread running through Zhou Yunxia's work, one that focuses on the mutations, loss of control, and speculative visions of the future within humanity, biology, and social forms. This tendency first emerged in his early works, which combined elements of Expressionism and Surrealism with a deep humanistic concern. Later works continued to feature images of creatures undergoing incubation or transformation. Even in pieces dominated by points, lines, and geometric planes, what is presented is not purely abstract visuality, but rather contains the implication of the aggregation, replication, and expansion of organic life.

Upon closer inspection of some of Zhou Yunxia’s abstract works, one can observe that the otherwise regular straight lines exhibit subtle fluctuations in certain areas. This is because they were drawn by hand, with minimal use of tools, and thus do not appear as mechanically sharp and straight. In 2016, Zhou Yunxia further innovated by using colored silicone as a medium for his paintings. This technique, which involves the hand-controlled injection of silicone instead of the traditional brush application of paint, results in a texture that possesses a more natural, organic quality.

Zhou Yunxia's artistic journey and body of work are rich and diverse, reflecting the constant inner drive that pushes him to explore and experiment, always striving for higher standards and greater artistic depth. He has never been content with the status quo in his art. Rather than calculating his position within the broader art scene, he always engages directly with his work, driven by a youthful mindset and an abundance of enthusiasm and energy.

Lacking the constraints and burdens that formal academic training can sometimes impose, Zhou Yunxia has been free to integrate new elements into his work without hesitation. This freedom has allowed him to expand his creative space beyond art itself, continually pushing boundaries. Even as an artist over sixty, Zhou maintains an exceptionally youthful attitude, unburdened by past successes or failures, and continues to elevate his standards and broaden his artistic horizons. This ability to keep evolving and pushing the limits is a rare and valuable trait. Given this, it is clear that Zhou Yunxia will continue to produce even more exciting and groundbreaking works in the years to come.